In this series we look at historical figures from China’s past who have intriguing Western parallels.

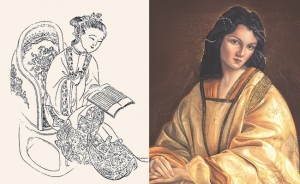

Today we take a look at two of the most legendary beautiful women in history. Although one is celebrated for her sacrifice for peace and the other remembered for the warfare caused by her affairs of the heart, perhaps both were walking predestined paths. Perhaps both were, even, emissaries of divine intervention.

Who were they?

Chinese lore tells of the Four Great Beauties—four women from different dynasties who were so stunningly beautiful that upon seeing them swimming fish would sink (Xi Shi), the moon would go into eclipse (Diao Chan), blooming flowers droop in shame (Yang Guifei), and birds in flight fall from the sky (Wang Zhaojun).

Wang Zhaojun was born over 2,000 years ago, during the Western Han Dynasty. Beyond her enchanting looks, she was also educated in the classic texts and renowned for her artistic talent. In time, the young lady was summoned to the imperial palace in preparation for becoming the emperor’s concubine.

Back then it was customary for imperial artists to paint portraits of the ladies in the harem for the emperor to choose from. Sadly, the court was being run by corrupt eunuchs, whom the young ladies would had to bribe for a chance at being selected. But Wang refused to resort to bribery. In retaliation, the artist added an unsightly mole to her portrait. Thus the emperor overlooked Wang and never bothered to see her.

During this time, China had been engaged in a bloody on-and-off war with a northern tribe. The emperor and chieftain finally agreed to resolve the conflict with a marriage treaty. The chieftain insisted, however, that he must have none other than the emperor’s daughter. Yet the emperor was not willing to part with his precious princess, and so ordered another woman be selected to take her place. The officials presented Wang’s unflattering portrait for approval, and he gave a nonchalant okay.

The emperor had no idea of Wang’s exceeding beauty until she was presented to the chieftain. But it was too late. She was whisked to the wild grasslands of the far north, never to return.

The chieftain was delighted with his end of the bargain. From then on, relations between his people and the Han improved remarkably, and peace prevailed for over half a century.

Wang Zhaojun forfeited her own future prospects for the welfare of her homeland. Simply put, her story is one of great personal sacrifice. And thanks to this one young lady, countless lives were spared.

Some folklore holds that Wang was a celestial fairy sent down from the heavens to bring the two nations to peace—that that was her mission.

As you may know, traditional Chinese culture believes that all events of historic importance are arranged by the gods and are under their deliberate guidance. This includes warfare and the rise and fall of dynasties. The emperor is also believed to be the Son of Heaven; he is chosen by the gods and must maintain the Mandate of Heaven. As such, a mortal person could scarcely manage to leave a mark on history or notably alter the grand script of history, unless he or she was fulfilling the will of heaven.

So from Zhaojun’s inborn gifts to each step that brought her to the palace and eventually led to a monumental choice, perhaps none of it was by chance.

Helen of Troy

Whereas Wang’s beauty could knock birds from the sky, Helen of Troy had a face that could launch a thousand ships. For centuries, she was repeatedly dubbed “the most beautiful woman in the world.”

The daughter of Zeus and the mortal queen Leda, Helen was a demigod. Her story, depicted in Homer’s the Iliad and Odyssey, has been rendered time and again in artwork, plays, and movies over three millennia.

Helen, the story goes, was admired by many powerful and influential men. It was King Menelaus of Sparta who won her hand, but she was later abducted and taken to Troy by the Trojan Prince Paris. Variations of the story abound: Was she powerlessly carried off, or did she in fact elope with Paris?

Whatever the case, the enraged Spartans set off in a thousand ships to attack Troy and retrieve Helen, launching the bloody ten-year Trojan War. In the end, Paris was killed in battle and Helen returned home.

However, what’s not as well known is that the husband of Helen’s mother (her stepfather King Tyndareus) once accidentally offended the goddess Aphrodite. The goddess put a curse on all Tyndareus’ daughters—both his own and Helen—dooming them to leave their husbands and become embroiled in multiple marriages.

And though it may appear it was Paris’ idea to go to Sparta—on pretense of diplomatic mission—in order to snatch Helen away, this was also preordained.

Prequel: In the Judgement of Paris, Zeus uses Paris to select the winner of a beauty contest between three goddesses—Aphrodite, Hera, and Athena. Each of the goddesses tempts Paris with a prodigious reward. But Paris chooses Aphrodite because she offers him the most beautiful woman in the world—Helen, stepdaughter of her old grudge Tyndareus. Throughout the story, Aphrodite ushers Paris and Helen to each other time and again. To complicate matters, the whole thing evokes the wrath of goddess Hera, who lost the above beauty contest. And when the queen of the Greek pantheon wants vengeance, she goes all out.

As ancient Greek history is much entwined with Greek mythology, it’s no surprise to find the Trojan War directed by the gods. So Helen could be interpreted as an actress in a great play of divine intervention involving Aphrodite who curses Tyndareus, Zeus who puts Paris in a tricky situation to judge the goddesses’ contest, Aphrodite who promises to reward Paris, and Hera who seeks revenge against Paris. And then many more Greek gods pitch in on both sides to help settle the score.

Well there you have it—two legendary beauties from the East and West, one who pacified a war and one who was the reason for starting one. Seeming parallels running in opposite directions, but once you factor in divine intervention, more similar than they appear.

We have one last pair of characters to go. Can you guess who they are?

Betty Wang

Contributing writer