Daily Life in the Tang Dynasty

If you’ve seen Shen Yun, you’ve definitely been for a visit to the Tang Dynasty. Spanning the seventh to tenth centuries, Tang China was the most powerful empire in all of Asia. It saw some of China’s greatest emperors, was the height of Chinese poetry, and built unparalleled prosperity, peace, and international influence. Its capital, Chang’an, was once the largest and most cosmopolitan city in the world.

Throughout the seasons, Shen Yun has produced many Tang Dynasty-inspired dances, featuring everything from indomitable imperial shieldsmen to court ladies in grand silk gowns. We’ve also had Tang story dances, like the many adventures of the Monkey King and Emperor Taizong’s encounter with the Shaolin monks.

As Shen Yun performers, we’re jumping in and out of the Golden Age every day. We may wake up to digital alarms, breakfast on almond butter banana overnight oats, and warm up using foam yoga blocks, yet when we step into our roles, we sync ourselves to the spirit of the ancients.

But what was it actually like to live during the Tang Dynasty? Let’s find out.

Dress

Clothing for normal folks was mainly made from hemp. They wore baggy pants, tunics secured with a sash, and sandals. On the other end of the spectrum, noblemen’s formal dress (tuxedo) was a silk robe with great hanging sleeves. Evening gowns for noblewomen were gorgeous flowing dresses with high waists and even wider sleeves, sometimes paired with sheer shawls. (You’ve probably seen these on the Shen Yun stage.) Aristocrats also often rode horseback and so wore deerskin or brocade boots, while the ladies fancied dainty embroidered flats.

Hair and Accessories

During the Tang, both men and women grew their hair long. Men pulled their hair into a single bun on top of their heads. Women, though, had many elaborate styles to choose from. They made multiple buns, braids, piles, spirals, and loops, and used decorated combs and pins to keep it all in place. Some hairdos took hours to style. (Makes Shen Yun performers’ 45-second quick-change between dances into a Tang Dynasty look seem more mind-blowing, no?)

It was custom for women to shave and redraw their eyebrows. In three centuries, dozens of styles went in and out of fashion—thin, thick, rounded, angled, squiggly, tapered, and splayed.

Tang jewelry wasn’t heavy on glittery precious stones like diamonds. Instead it was fashioned from pearls and jade. Jade stood for purity, rectitude, wisdom, and courage; and its durability symbolized immortality. Pearls were believed to be created by the moon and nurtured by the sun, containing essence of both. The iridescent feathers of the tiny kingfisher was another favorite and precious jewelry inlay; under different lighting, it resembled turquoise or lapis lazuli.

Mirrors back then were made of burnished bronze. From time to time, these mirrors dimmed and had to be taken to craftsmen to be refurbished with a grindstone.

Instead of spray perfumes and stick deodorants, people slung aroma pouches on themselves. To freshen their breath, they chewed on honeyed Chinese olives (gum) or ate cloves (mints). They soaked in scented baths fragranced with ancient bath bombs of aloeswood, frankincense, sandalwood, camphor, and chrysanthemum.

Around the House

Windows during the Tang Dynasty had wooden lattices featuring a variety of geometric patterns and bas-relief carvings. Some even contained inlaid minerals. These lattice windows were highly decorative and also very necessary, because they supported panes that were made not from glass, but paper or silk. Basic paper windows were oiled to be more translucent. Deluxe silk windows were dyed, so that the light shining through them would be tinted and color the room.

During early Tang, people sat cross-legged on low platform-like couches without backs or armrests, and used low tables. Around mid-Tang, chairs from the West—higher and with backs—became common, as well as stools and benches. Tang beds were canopied and looked like poster beds. Pillows were not of feather or down, but hard and indented to cradle your head. These wood, porcelain, or stone pillows helped maintain the hairstyles that took hours to do. The Tang also lit scented candles and braziers in the bedrooms to aid relaxation and sleep. Some candles had markings that were used to keep time.

City Life and Shopping

Chang’an, the Tang capital, was like an ancient NYC. It was one of the greatest cities in the world, and the eastern terminal of the Silk Road. Chang’an had a large foreign population, and quite a cosmopolitan vibe. Exotic things were in: horses from Karashar, goblets from Byzantium, silverware from Persia, carpets from the Red Sea coast, indigo and pistachios from Samarkand, ginseng and pine nuts from Korea, grape wine from India, whirl dancing from Sogdia, and it was vogue to dress like the Central Asians. (Leopard-skin hats!)

Chang’an had a checkerboard layout, with main avenues marking 108 city wards. Of the numerous street vendors, shops, and marketplaces big and small, the two most prominent were the East Market and West Market. According to historical records, West Market had 40,000 shops dealing in 200 types of trade!

You could find locally produced goods and exotic foreign products—groceries, livestock, medicine, spices, textiles, jewelry, hardware, musical instruments, game boards. There were services like restaurants, inns, banks, and fortunetellers. You could even rent a donkey if you were tired of walking or carrying your bags.

Today in Chinese, going shopping is still called mǎi dōngxi, literally Buying East and West, after the two main markets of Chang’an.

The government regulated price and quality control, and ersatz merchandise could be confiscated. Earlier on, officials also enforced strict curfew laws. Markets had to open at noon and close at dusk. City and ward gates were locked at night. Even in case of emergency, civilians had to get permission from the night patrol to go out.

As laws became less stringent, lively night markets popped up within communities. You could get stuffed pancakes from cake stands or exotic pastries from pie shops, and you could stop by teahouses or Central Asian eateries. So the night markets that Shen Yun performers love visiting in Taiwan, Japan, and Korea—and you’ve probably seen our photos of marinated skewers and shaved-ice piled high with toppings—actually go back to Tang China!

Money

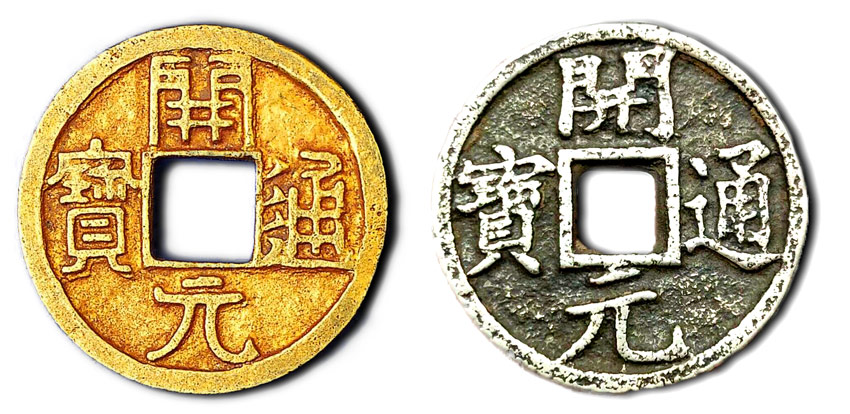

Tang currency included gold and silver bars and copper coins, which were round with a square hole so they could be strung together for convenience. Silk cloth was also used as money. There was even a tax that citizens had to pay in bolts of silk.

Travel

During the Tang Dynasty merchants traveled through vast trade networks. They sailed to India, Southeast Asia, Persia, Africa, and went all the way to Europe along the Silk Road. A round-trip to Rome took two years.

On route, there were strict border controls that you had to have travel permits to pass through. For security purposes, armor, crossbows, military books, and even star maps and astronomical instruments were prohibited.

Temples

Buddhism thrived for most of the Tang Dynasty and became a major religion. In time, Buddhist temples and monasteries developed into more than places of worship. Throughout the empire they served as schools, hostels, and venues for gatherings and events. Some provided medical care. Some operated local mills. Some helped keep safe-deposit boxes.

Gameplay

In 2020, soccer (or football, if you prefer) is the world’s most popular sport. Back in the Tang Dynasty, they enjoyed archery, hunting, polo, but most of all cuju, which was played by people of all classes. And guess what? It’s actually an ancient form of soccer! Before the Tang Dynasty, cuju balls were leather and stuffed with feathers. During the Tang, an upgraded air-filled ball was invented.

Polo, on the other hand, came from Persia. It was a favorite of the nobility, and even many emperors were big fans.

Beverage

Nowadays, supermarket aisles are loaded with spring water, mineral water, electrolyte water, sparkling water, artesian water, and more. Tang people were particular about their water too. Tang medical texts catalogued many different types. For example: autumn dew improved facial complexion, melted frost dispelled internal heat, and water that flowed through prized minerals (jade or limestone stalactites) prolonged life. And don’t drink melted snow in the springtime, unless you want to get sick.

Tang people boiled, strained, and dried fruits like jujube dates, crabapples, and apricots into powdered juice mixes. They fermented wine mostly from rice, but also fruits like grapes and pears.

Tea, however, became the national drink, especially after the first monograph, The Classic of Tea, was written in the eighth century. The treatise describes the mythological origins and history of tea, methods and tools used for cultivating, preparing, and drinking tea, plus tea-related poems, customs, recipes, and more.

The Golden Tang

The Tang Dynasty ruled China for three hundred years from 618 to 907. It covered over 4 million square miles, stretching from the Tarim Basin of Xinjiang to the Korean Peninsula, and from the steppes of southern Mongolia to Vietnam. And Tang society and culture were highly diverse.

As such, it would take ages to get a complete picture of life during the Tang. We haven’t even touched upon poetry, performing arts, education, family life, or cuisine. How did they celebrate birthdays? And what were the emperor’s street carnivals like?

Nevertheless, we hope this taste gives you an inkling of what life was like back then. And maybe next time you attend a Shen Yun performance you will enjoy our Tang pieces with more insight.

Sometimes, 21st century life with its technology at every turn makes you want to escape to simpler times. So if you want a mini old-world retreat, take a leaf out of the Tang Dynasty book—brew a pot of tea and sip it slowly without multitasking, kick a soccer ball around the backyard, or visit an open-air market instead of ordering groceries online. And enjoy the fact that you’re unplugging and reacquainting with not only real life, but Golden Age-life.