A Story of Selfless Beauty

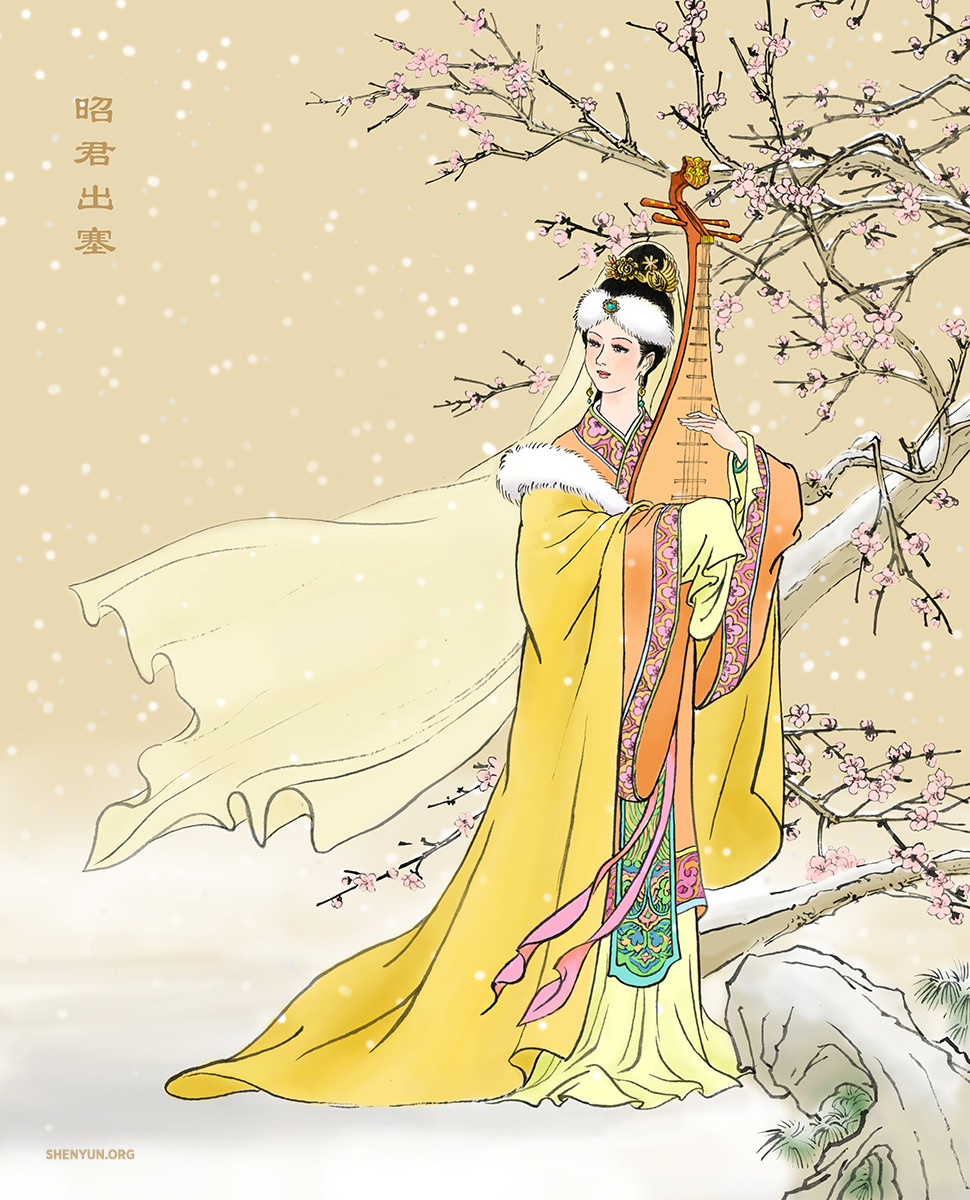

One of ancient China’s Four Beauties is often depicted atop horseback with a fur-lined travel cloak draped over her shoulders. In her arms, she cradles a precious pipa, and, in her eyes, an unswerving determination holds back the tears.

Where is she off to? Why is she dressed this way? And what song flows forth from her heart?

Wang Zhaojun was a daughter of the Western Han Dynasty, in the first century B.C.E. Since youth, her exceptional beauty, intelligence, and numerous talents were renowned across the land. Some folk legends say she was a goddess sent by the heavens with a special mission—to bring stability to contentious nations and happiness to their peoples.

A Gem Forsaken

Zhaojun was born into a family of high esteem. From a young age, she became well-versed in the classics, mesmerized listeners with the four-stringed pipa, and was also adept at the Four Arts of the Chinese Scholar (the Chinese zither, the strategy game Go, calligraphy, and painting).

It could only be expected that when Emperor Yuan passed a decree summoning elite women from across the empire to enter the inner palace, Zhaojun was the top choice to represent her district. And though she was grieved to leave her parents and they her, the edict had to be obeyed.

According to custom, when selecting a new concubine, the emperor would consult the portraits of the women in his harem. Unfortunately, these portraits were often done by greedy painters who weren’t above embellishing a candidate’s painting if she slipped him a handsome gratuity. Zhaojun did not want to resort to such means. So although she possessed sublime beauty and brilliant talents, she was passed over in the selection process. Subsequently, she remained a minor lady-in-waiting for some lonely years, completely unnoticed by the emperor.

Difficult Neighbors

On the windswept steppes beyond China’s northern borders lived nomadic people called the Xiongnu. They were a host of tribes that united just before the beginning of the Han Dynasty. As a confederation, the Xiongnu were powerful and intimidating. Sometimes, they chose to trade—horses and livestock for Chinese tea, distilled beverages, rice, and silk. Other times, they chose to pillage and raid. Han emperors tried different methods of coping, including dispatching troops to fight and sending envoys to negotiate peace. It was a strained relationship.

In 33 B.C.E., the Xiongnu chief Huhanye Chanyu visited the Han capital to pay homage and to bolster the relatively pleasant relations that existed at the time. In return for his tributary offerings, he received generous rewards from the emperor. However, what he really wanted was the hand of a Han princess; he wanted to become an imperial son-in-law.

Three times he got down on one knee and appealed to the Han emperor. But there was no way the emperor could hand his princess—the apple of his eye—over to the nomads. His majesty grew more and more distressed until he remembered that for the purpose of marriage alliances, emperors before him would confer the title of “princess” onto a daughter of the imperial clan or a palace lady. He decided to do the same.

After consulting his advisors, Emperor Yuan agreed that any garden-variety court lady whom he’d never laid eyes on would do… Can you guess who?

The Choice

At this point, the Han Dynasty was quite the place to be. Confucianism was in. Civil service examinations were expanding. The invention of an early form of paper promoted literacy and art, and fu rhymed prose flourished. The capital of Chang’an had nine government-controlled markets. The well-to-do could procure luxury merchandise from skilled artisans made of gold, silver, bronze, jade, lacquer, and ceramic. They enjoyed a diverse diet of rice, wheat, barley, millet, soy, and lentils; noodles, breads, and cakes; beef, lamb, pork, chicken, duck, pheasant, deer, and fish. They seasoned dishes with ginger, cinnamon, honey, sesame, Sichuan pepper, and caraway, and indulged on lychees, jujube dates, pomegranates, plums, and more. It was a time of progress and prosperity.

By comparison, the Xiongnu lifestyle seemed bleak. Who would want to be banished to the cold and unforgiving steppes, to eke out a grim existence inside a makeshift yurt, and tend to livestock day in and out? Even being made a princess couldn’t put this final destination on anyone’s bucket list.

Yet, when approached, Zhaojun thought about all that her decision would impact beyond her own happiness. She did think of her family, her parents and brothers, and about leaving the Great Han Empire—traveling beyond the edge of “civilization” into the unknown, to live forever among foreign people with foreign customs speaking foreign tongues. But she also thought about what a successful marriage alliance would mean for the Great Han. And she steadied her heart.

On the eve of the Xiongnu delegation’s departure, the emperor decided to look in on the court lady who agreed to be wed off. Yet the maiden who greeted him was not plain and unremarkable. She possessed an otherworldly beauty that made his heart leap. And she carried a sublime demeanor that took his breath away.

What is your name, again? When did you enter the palace?

…You can’t be presented to the Xiongnu! This isn’t right?!

The emperor set off to find his advisors. Yet, the first people he ran into were his wife and daughter. Sensing the emperor’s change of heart, the two threw themselves at his feet in great distress.

Father! It has to be her!

Your Majesty! You wouldn’t banish your own daughter to the barbarians?

I beg you!

The emperor wavered. He felt exasperated that he was about to lose such an incredible woman from his harem. After seeing Zhaojun, he wanted to make her his newest concubine—perhaps his favorite concubine. Yet he couldn’t retract his promise to the Xiongnu chief. And giving his own daughter away was out of the question. With a heavy sigh, the emperor buried any thought of keeping Zhaojun in the palace.

As for those swindling courtiers who kept Zhaojun hidden away all these years, they would be properly dealt with.

Queen of the Steppes

The Xiongnu chief, on the other hand, was delighted that the emperor had granted him the most heavenly woman he had ever seen. And early next morning, the nomads departed ceremoniously with their new queen.

This is where the popular image comes in—Zhaojun donning a long travel cloak and making her way toward the northern frontier. Although she was resolute to serve her country, it still wasn’t easy to go. As her horse let out a plaintive neigh, an unswallowable lump formed in her throat and tears welled in her eyes.

Once Han China disappeared beyond the horizon, Zhaojun unwrapped her pipa, and a most emotive melody issued forth. It is said that a flock of geese flying overhead were so captivated by her beauty and her song, they forgot to flap their wings and dropped straight out of the sky. This story gave rise to “Fallen Geese”—a quirky-sounding allusion to the elegant Zhaojun.

After arriving on the steppes, Zhaojun soon adapted to the nomads’ lifestyle and became their endeared matriarch. She never forgot her homeland, though, and always urged Xiongnu leaders to maintain peaceful relations. She taught the Xiongnu about Han laws, customs, and culture, and remained with them for the rest of her life, even after her husband’s death. Subsequently, there were no wars between the two kingdoms for six decades—a remarkable feat.

The Four Beauties of ancient China were not only exceptionally gorgeous, but also remarkable women who had major influences on Chinese history. Of the four, Zhaojun is remembered for her selfless sacrifice. Some consider her contribution equal to that of the Han Dynasty’s greatest generals.

In two millennia, her story has been retold time and again, including by the legendary poet Li Bai, who wrote:

The moon above the Han palace and land of Qin

Sheds a flood of silvery light, bidding the radiant lady farewell.

She sets out on the road of the Jewel Gate, a road she will not travel back.

The moon above the Han palace rises from the eastern seas,

But the radiant lady wed in the west will return nevermore.

Shen Yun’s 2021-2022 The Story of Lady Wang Zhaojun has brought a dance rendition of her tale to the world stage.